Chevron weighs extending CEO Mike Wirth past mandatory retirement age

Maria Bartiromo goes one-on-one with Chevron CEO on green energy transition

Chevron chairman and CEO Michael Wirth calls for policy that incentivizes investing for renewable fuels today and the technologies of tomorrow on ‘Maria Bartiromo’s Wall Street.’

Chevron Corp.’s board of directors is considering waiving the company’s mandatory retirement age for Chief Executive Mike Wirth, a move that would allow him to remain CEO for a longer period, people familiar with the matter said.

Some board members have said the San Ramon, Calif., oil company doesn’t have an internal candidate ready to succeed Mr. Wirth, who would reach the company’s fixed retirement age of 65 in late 2025, and that additional time would allow him to prepare a successor. The board members have also said they see no reason to push out an executive who has performed well, the people said.

Chevron’s board is undertaking the years long process of succession planning as it faces the geopolitical uncertainty of the war in Ukraine, prospects of an economic slowdown and potential oil-market turbulence, as well as political pressure from the U.S. and Europe to prepare for a future that depends less on fossil fuels.

A Chevron spokesman declined to comment.

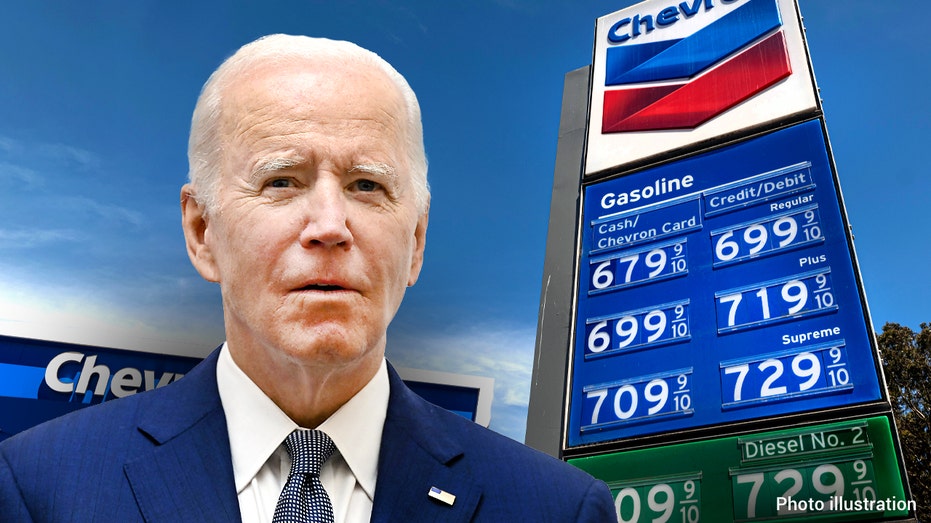

Michael Wirth, chair and CEO Chevron Corp., speaks during an interview on CNBC on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in New York City, March 1, 2022. (Brendan McDermid / Reuters Photos) Mr. Wirth, 62 years old, an engineer and Chevron employee for over 40 years, became chairman and CEO in 2018. At the time, Chevron had been struggling for years from project-cost overruns and its profit was laid low by an oil-market crash. Mr. Wirth was seen as a cost-conscious executive, having led the company’s refining and chemicals business—in which margins are critical— for almost a decade. As of the fifth anniversary this month of Mr. Wirth taking the helm, Chevron’s shareholders have seen a total return of 70%, compared with about 71% for its U.S. rival Exxon Mobil Corp. over the same period, and about 23%, 31% and 65% for its European counterparts Shell PLC, BP PLC and TotalEnergies SE. Chevron vowed last month to repurchase $75 billion in shares—about a fifth of its market value—over the next several years, a move that was criticized by the White House, which argued it should spend the money on production to lower energy costs. Chevron Corporation In 2019, Mr. Wirth refused to enter a bidding war when Occidental Petroleum Corp. swooped in to buy Anadarko Petroleum Corp. for billions more than Chevron had offered. Chevron received a $1 billion breakup fee and bought Noble Energy Inc. for a far lower price the next year, a deal that gave the company access to Middle East natural-gas markets and a bigger U.S. footprint. Mr. Wirth’s Chevron has also benefited from the income of investments the company made years ago, such as the over-budget Gorgon liquefied natural gas export project in Australia, and from high oil and natural-gas prices that lifted Chevron’s annual profit last year to a record $35.5 billion, making it America’s seventh-most prosperous company in fiscal 2022. CHEVRON CEO DENIES BIDEN OIL LEASE CLAIM, DETAILS PRACTICAL ENERGY POLICY Nigel Hearne, who oversees Chevron’s upstream, midstream and downstream units, has been seen as the foremost contender to eventually succeed Mr. Wirth, according to the people familiar with the matter. Jeff Gustavson, head of Chevron’s lower-carbon energies business, and Eimear Bonner, the company’s chief technology officer, are also considered contenders, the people said. The three executives didn’t respond to requests for comment. The Chevron logo appears above a trading post on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on Oct. 8, 2019. ( AP Photo/Richard Drew, File) Before the 1980s, many of the top executives of Chevron’s predecessor company, Standard Oil Company of California, held the CEO position for shorter-term stints, typically around half a dozen years. Then a wave of big mergers happened, and executives began staying for much longer to oversee the company’s transformations. George Keller, who was the head of SoCal when it merged with Gulf Oil in a 1984 deal that created Chevron, served about a decade and reached the company’s mandatory retirement age of 65 in 1988. The company appointed a successor, to take over at the start of 1989. Companies had put such policies in place as a check on the influence of CEOs over boards of directors. Since then, Chevron’s CEOs have held the position for around eight to 11 years, including Kenneth Derr, who succeeded Mr. Keller, David O’Reilly, who oversaw the company’s merger with Texaco Inc., and John Watson, Mr. Wirth’s predecessor. EXPERTS RIP BIDEN ADMIN AS US OIL GIANTS BET BIG ON AMERICAS: ‘WHITE HOUSE LAMPOONING OUR OWN INDUSTRY’ Mr. Wirth is in his fifth year as CEO. Chevron might join a growing list of high-profile companies that have waived, adjusted or done away with a mandatory retirement age for top brass, including most recently retailer Target Corp., construction equipment maker Caterpillar Inc. and aerospace manufacturer Boeing Co. Mr. Wirth’s tenure has tested his skills navigating crises such as the historic oil downturn in 2020 and questions about the long-term future of fossil fuels. He is seen by many in the industry as an effective public emissary as it faces intense criticism from the Biden administration and other Democrats. Fuel prices at a Chevron station in San Francisco, California, on June 9, 2022. (David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images / Getty Images) In a letter to President Biden last year, Mr. Wirth chided the administration’s attempts to sometimes "vilify" the oil industry and said the U.S. energy sector needs clarity and consistency on policy matters. Matteo Tonello, managing director at nonprofit research group The Conference Board, said more companies have quashed those rules as boards have become more independent because it ties their hands unnecessarily in succession planning. "The prevailing view today is that boards have the competency and skill sets to develop a strong succession plan," Mr. Tonello said. Some boards are also holding off on succession planning as they face significant headwinds, such as rising interest rates, the war in Ukraine, the possibility of an economic recession and ongoing snarls in the world’s interconnected supply chains, said Cathy Anterasian, a consultant who leads CEO succession services for executive search firm Spencer Stuart. CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX BUSINESS APP "This isn’t a great environment to drop in a brand new CEO," she said. "Another year or two of development would accelerate readiness [of companies’ internal candidates] and make the board more confident in that decision." Source: Read Full ArticleTicker Security Last Change Change % CVX CHEVRON CORP. 171.97 +3.53 +2.10%