The death of Desmond Tutu has taken a great leader from the world

With the passing of Desmond Mpilo Tutu at the age of 90, the world has lost a great leader, a man who used his position within the church and his towering moral authority to help end South Africa’s racial segregation. Archbishop Tutu led with clarity of purpose, never swaying from the pursuit of justice and equality for all. And, as South Africa sought to heal in the aftermath of apartheid, he urged forgiveness, truth-telling, compassion and reconciliation.

Using his influence as a regional bishop, archbishop of the nation’s Anglican Church, the head of the South African Council of Churches for six years and an international professor of theological studies, Desmond Tutu denounced segregation and the draconian security laws imposed by the then-ruling National Party. His techniques of persuasion were simple logic and moral precision, topped by a dose of infectious laughter and gentle humour.

Archbishop Tutu rose to prominence in the 1970s, when South Africa was riven with violent protest against the apartheid system. The state imposed increasingly harsh security laws, while police and security forces were brutal and occasionally murderous. Frustrated by the lack of international concern about apartheid, he took to the world stage, urging foreign governments to help eradicate the regime by isolating South Africa through economic sanctions. In his view, supporting the economy of a nation that deliberately tramples its citizens’ most basic human rights has the effect of bolstering the state’s unjust policies.

When awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, he spoke of “a land bereft of much justice, and therefore without peace and security”. He described a nation at war with itself and with the world, a country where unrest would continue “until apartheid, the root cause of it all, is finally dismantled”.

Yet even this honourable, religious statesman and peaceful warrior was drawn to wonder about the efficacy of non-violent protest under South Africa’s intractable white minority regime. At the time, he acknowledged that revolutionary elements of the African National Congress (led variously by Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo for more than 40 years) and the Pan-Africanist Congress might consider violence “a last resort for them”.

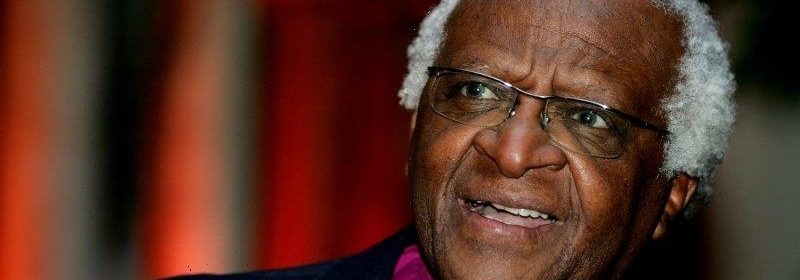

Archbishop Desmond Tutu in Cape Town in 1994 with Nelson Mandela.Credit:AP

A year later, he conceded: “I am surprised that radical Blacks are still willing to say that we are their leaders. What have we got to show for all our talk of peaceful change? Nothing.” Indeed, it would take another four years for then-president F. W. de Klerk to willingly and sincerely open discussions to end segregation and begin fundamental changes to enfranchise all South Africans of any colour or birth heritage.

Throughout his life, Archbishop Tutu robustly confronted the powerful, the racists, the corrupt and the hypocrites. He castigated violent black protesters who used awful methods of murder and torture to exact revenge on political rivals or suspected police informers.

In recent years, he acerbically criticised the ANC government when it was led by Jacob Zuma, saying it was “worse than the apartheid government – because at least you knew you were expecting it from the apartheid government”.

For Archbishop Tutu, human rights meant “the right to a fulfilled life, the right of movement, of work, the freedom to be fully human”. Beyond the apartheid cause, he perceived lasting threats to human rights through the inequitable distribution of our planet’s resources and the failure of governments to act determinedly on climate change.

The Nobel Prize committee specifically noted in 1984 that the award to Archbishop Tutu was one to be shared with “all individuals and groups in South Africa who, with their concern for human dignity, fraternity and democracy, incite the admiration of the world”.

A generation of leaders who drove the anti-apartheid movement is passing on. They taught the world how to endure when it seemed no one was listening and hope seemed lost. Their goals were founded on the honourable ideal of human dignity and equality.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article