RICHARD KAY pays tribute to Soho bon viveur Naim Attallah

Bon viveur who revelled in his ‘harem’ of society beauties including Nigella Lawson: As Naim Attallah dies aged 89, RICHARD KAY pays tribute to the man who ran the Queen’s jeweller and sexed up the world of books

Beyond the incestuous world of books, his was not a household name. To the publishing trade, however, Naim Attallah, who has died aged 89, will go down in history as a genius who ‘sexed up’ its stuffy reputation and gave the industry a much-needed kick up the backside.

He did so with a combination of business acumen, charm and studied eccentricity.

From the mismatched socks, to the dressing gown-style coat he wore to lunch in his favourite Soho restaurants — with two watches he would flash on each wrist — the erudite Attallah was a man who liked to stand out in a crowd.

And in the 1980s and 1990s he seemed to be everywhere, his tall patrician figure a regular presence at launch parties and theatrical openings. As publisher of Quartet Books, which he bought in 1976, he was a godfather figure to a generation of clever — and invariably pretty — young women.

For many years he was the driving force behind Asprey, the Queen’s jewellers, and the publisher of two of Britain’s most idiosyncratic magazines, The Literary Review and The Oldie.

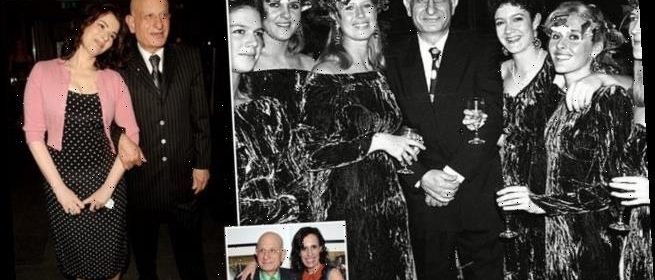

Erudite and droll: Naim Attallah with Nigella Lawson. She was one of his most prominent employees, but he also drew well-bred figures such as Winston Churchill’s granddaughter Emma Soames, Lady Cosima Fry, Virginia Bonham-Carter and Jenny Aeron-Thomas

He was also a compulsive risk-taker, investing in films — one such production was visited by the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret — West End plays, fashion collections and the fragrance business. He liked to gossip and was a frightful name-dropper, but he was a droll story-teller with a voice that could reach a chandelier-shattering squeaky pitch, along with constant finger-prodding.

And he could be startlingly direct: on one occasion asking the aesthete and homosexual scholar Sir Harold Acton if he had ever held a naked woman in his arms, drawing the confession that indeed Acton had — a young Chinese girl.

On another he infuriated the mystic and explorer Laurens van der Post by accusing him of embroidering his gruelling adventures in African deserts.

But it is perhaps his role as a ‘collector’ of much younger women that earned him both admiration and opprobrium in equal measure. Almost every beauty with a double-barrelled name or famous father found a berth on Attallah’s payroll.

‘Naim’s harem’ was the title bestowed by newspaper columnists on the extraordinary slew of ‘posh totties’, often with literary aspirations, who went to work for Quartet in the 1980s.

Nigella Lawson was one of his most prominent employees, but he also drew well-bred figures such as Winston Churchill’s granddaughter Emma Soames, Lady Cosima Fry, Virginia Bonham-Carter and Jenny Aeron-Thomas (of whom Attallah said, ‘tall and slender with fabulous legs, blonde hair and a gorgeous bosom’).

‘Naim’s girls’ were part of London’s social season and occupied a demi-monde of unbridled loucheness. Some were encouraged to wear rubber dresses for launches (among them Princess Katarina of Yugoslavia) and they provided the satirical magazine Private Eye with a never-ending fund of stories about ‘Naim Attallah-Disgusting’.

As one member of the gang Sophia Watson, granddaughter of writer Evelyn Waugh, put it: ‘We were young, pretty, had “names” and we loved parties. We were not paid very much but we certainly enjoyed ourselves.’

She said there were claims ‘he employed us to counteract Quartet’s Left-wing reputation, which may have been true, but it was no secret that he also wanted to surround himself with beauty’.

Not everyone fell for his blandishments, however. One well connected figure, Sonamara Sainsbury, walked out on him, even failing to attend the farewell lunch he had arranged in her honour.

Attallah pictured with a bevy of young women in October 1987. He will go down in history as a genius who ‘sexed up’ the publishing trade’s stuffy reputation, writes Richard Kay

So was there a dark side to the Palestinian-born polemicist, who came to London at the age of 18?

At the launch of his 2019 book, A Scribbler In Soho, a celebration of his friend Auberon Waugh, the film director Chloe Ruthven, a niece of former arts minister Lord (Grey) Gowrie, led a one-woman protest. The gist of her complaint was that she had been invited to Attallah’s house in France but once there he allegedly attempted to ‘paw’ her.

Another troublesome brush came when a former employee, Jennifer Erdal, brought out Ghosting, a ‘fictional memoir’ of her 17 years working for a publisher called ‘Tiger’ who produced several books under his name, despite the fact that she had written them.

Jennie had been Attallah’s assistant for years and reviewers jumped to the conclusion this was a factual account. It was a betrayal that cut him deeply. He later wrote: ‘The word “regret” has never had a place in my vocabulary, yet it is the only word to use on this single sad occasion. I would never dispute the fact that the finished books were realised through her writing . . . Her version . . . can only suggest a large measure of ill-will towards me, in spite of the many years of our friendship and close working relationship . . . A vow had been broken . . .’

Of his relationships with women, Attallah insisted he was a flirt but didn’t have affairs. When his wife Maria, with whom he had one son, fell ill, he was devoted to her care until her death in 2016.

A life-long teetotaller, Attallah was born in Haifa, the only son of a Barclays Bank cashier, and raised in a household of women, attending a convent with his sisters.

He dreamed of being a journalist, but after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 he instead came to Britain to study engineering at Battersea Polytechnic.

He did not finish his course, instead taking a string of manual jobs. Through contacts he arrived in the City and began to make a name for himself.

He became close friends with John Asprey, heir to the jewellery company, and after becoming group chief executive oversaw a massive expansion.

Turnover rocketed from £2.8 million a year to over £200 million. But after rescuing the company and 21 years’ service, he was forced out following a downturn, another betrayal he felt sorely.

Meanwhile, he had begun to buy his way into literary London. Along with Quartet, he established The Woman’s Press and even launched perfumes.

For all his high-minded literature, it was the tomes about sex that made him money.

Naked London, published in 1987, featured a lot of people with no clothes on. It included aristocratic beauties such as Sabrina Guinness, Andrea von Stumm and Sophia Sackville-West.

Publisher Attallah pictured with author Lauren Goldstein Crowe at the launch party for ‘Isabella Blow A Life in Fashion’ in Covent Garden, London, in February 2011

The ebullient Jubby Ingrams — daughter of former Private Eye editor Richard (she tragically died in drug-related circumstances) — gave Attallah her naked Polaroids from the shoot for safe-keeping.

He hid them in his wallet ahead of publication of the book only for them to flutter out during a visit to see his bank manager.

He later imagined the manager thinking: ‘Who is this seedy customer carrying about photos of naked young women — some sort of sex maniac?’ A notion Attallah would always disavow.

His most recent autobiography, published two years ago — shortly after he was awarded the CBE for services to literature and the arts — is a name-dropper’s paradise. From Billy Connolly and the Bee Gees, to Paula Yates and Dame Margot Fonteyn for whom ‘sex had been her driving force’.

One way of getting to know such luminaries better was to publish books by or about them.

Seeing ‘divine’ Charlotte Rampling in the film The Night Porter, Attallah commissioned a coffee table tome in her honour.

Many of Attallah’s views would seem strangely unfashionable to the post-MeToo generation, but his death robs the literary world of one of its most extravagant and larger-than-life figures.

Source: Read Full Article