Women in science not lifted by decade of investment

Key points

- Australian government data shows the number of women working in STEM jobs has barely increased since 2009.

- However, enrolments in STEM education have dramatically risen.

- The government’s Women in STEM Ambassador suggests we’re focussing too much on getting women into STEM education, not helping them build good careers.

A decade of investment has barely increased the number of women working in science and engineering – leading the government’s Women in STEM ambassador to declare that “people have to pull their finger out, frankly”.

Women are enrolling in STEM courses at universities in dramatically greater numbers, but that is not translating to lengthy careers: the percentage of women working in science, technology, engineering and maths jobs rose from 11 per cent in 2009 to just 15 per cent in 2021, government figures released last week show.

The figures suggest the tens of millions of dollars spent and the hundreds of initiatives in government and industry are not working to address the whole issue, Professor Lisa Harvey-Smith, the federal government’s Women in STEM ambassador, said.

“The vast majority of people are trying to tackle a very small sliver of the issue – which is the pipeline of young people. That does not address the core issue: lack of respect for women, and discrimination and harassment in the workplace,” she said.

“They are over-reliant on supporting individuals to navigate a broken system, rather than fixing the problem. Until organisations actually tackle those fundamental issues within their workplaces, it will not be possible for them to recruit these highly qualified women that exist already.”

Government efforts to get women into STEM jobs gained serious momentum in the middle of the past decade: Malcolm Turnbull invested $13 million in 2015 and the Morrison government launched a 10-year plan in 2018.

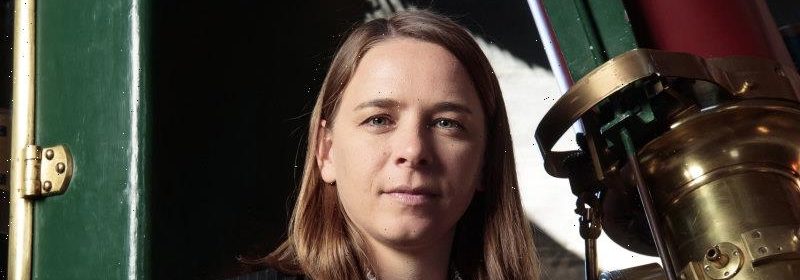

Professor Lisa Harvey-Smith Credit: Supplied

But these efforts remain largely unco-ordinated, with more than 330 separate initiatives across Australia, and many not based on solid evidence, Harvey-Smith said.

“I have seen things as absurd as teaching women to play golf so they can be part of the old boys’ network. This is really badly thought-out stuff. Instead of turning women into men, we need to fix the structural problems we have as a society, and treat these programs scientifically.

“People have to pull their finger out, frankly,” she said. “It’s the same with International Women’s Day and cupcakes and panel sessions. Stop discussing the issue and admiring the problem.”

Science Minister Ed Husic announced a review of the federal government’s Women in STEM program this month. The latest data “underline the importance of why a renewed effort is needed to break down structural barriers”, he said in a statement.

The number of women enrolling in STEM courses has increased 24 per cent since 2015. But the gender pay gap is larger in STEM than the workforce average – so when these women get jobs they soon find themselves earning less than their male peers, said Dr Sherry Bawa, a Curtin University researcher who studies the problem.

And when women need to take a career break – to have a family, for example – they find they get shunted from working with a microscope to working with a computer.

“Even the women we have in STEM careers, we are not using their potential,” Bawa said.

Professor Andrew Norton, a university policy expert at the Australian National University, said that in other cases, the jobs did not exist at all, with a chronic shortfall in job opportunities in science compared with university enrolments.

“It is not ‘gender equity’ to encourage women to take courses that do not lead to jobs that will use their knowledge and skills,” he said.

A study published in the UNSW Law Journal on Monday found female inventors were less likely to be awarded a patent than male inventors. As more women were added to a patent application, the chances of success fell further.

Dr Vicki Huang, the Deakin University researcher who led the study, said: “If you’re an inventor, having a patent means you get more access to capital, you get promoted. It has this compound effect on your career.”

For these reasons women struggle to progress through their career into leadership. In science, for example, 49 per cent of the workforce is female – but just 24 per cent of executives are.

“Who’s on the promotion committee? A lot of these boards tend to be male dominated,” says Dr Marguerite Evans-Galea, spokeswoman for the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering. “We need to accelerate this change. We don’t want to be waiting another 100-plus years.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article