South Africa: Farm where Nelson Mandela started anti-apartheid journey risks closure ‘because of pandemic and corruption’

There are no fields or streams on display as you travel down the road to Liliesleaf farm.

Instead, the property has been completely enveloped by the suburban sprawl of northern Johannesburg.

But the fact that this unfashionable structure still occupies a patch of South Africa‘s largest city speaks volumes about the role it played in the formation of modern, democratic South Africa.

It was at this unremarkable farmhouse that a collection of activists and idealists – both black and white – held key debates and meetings based on one critical idea.

They used Liliesleaf farm as a secret base to plot the downfall of the apartheid regime.

Together, they formed a who’s who of the liberation struggle, including Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Joe Slovo, Denis Goldberg, Govan Mbeki (father of president Thabo Mbeki) and a so-called houseboy named Nelson Mandela.

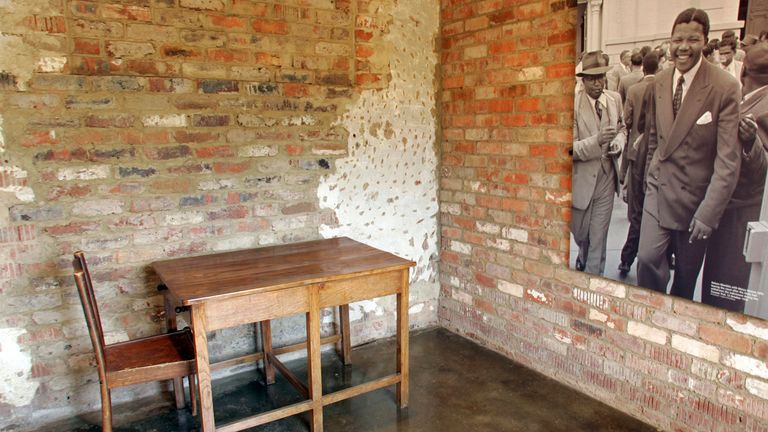

“Liliesleaf was an old house that needed work and no one lived there. I moved in under the pretext that I was a houseboy or caretaker that would live there until my master took possession… I wore the simple blue overalls that were the uniform of the black male servant,” wrote Mandela in his book, Long Walk To Freedom.

A man called Harold Wolpe purchased the house in 1961 for the underground South African Communist Party and his son, Nicholas, now heads the organisation which runs the property.

When we found him at Liliesleaf however, he was slumped in a chair next to the ticket booth and there was not a single visitor to be seen.

I asked him what was going on.

“We’re closed,” he said. “I don’t have money to pay for the staff and you can’t expect them to work for nothing can you? If they don’t come, we can’t open it, who is going to interact with the guests? It is the only option I had.”

He told me the government had refused his pleas for financial support after a series of COVID-related lockdowns destroyed the organisation’s revenue base.

“Sooner or later there will be no historic sites, no museums, no theatres and eventually there will be nothing left for us to protect because they will have all disintegrated into wilderness.”

When Mr Wolpe went public with his criticisms, decrying the “abject failure” of the country’s arts of culture department, officials fired back, accusing farm managers of misusing 8.1 million rand (£400,000) donated by the department for the renewal of exhibition infrastructure in 2015.

Mr Wolpe says he had to use the money for operational costs and questions why the department is raising the issue now.

“There have been times where I have wanted to burst out crying because… we have been able to stay above (allegations of corruption) for the last 19 years, that toxicity, the corruption and maladministration, we have managed to stay away from and now we find ourselves embedded, now we are in the middle of it.”

Allegations of corruption and shoddy administration are widespread and go to the top – and the heart of South African society.

Former president Jacob Zuma faces 16 counts of corruption, racketeering, fraud, and money laundering in relation to a £1.4bn arms deal with French manufacturer Thales.

He and his lawyers have managed to delay the trial for over 16 years by deploying a so-called “Stalingrad-approach”.

Zuma was sentenced to 15 months in prison in June after failing to show up to a commission of inquiry into corruption that he appointed when he was president.

Controversially, he was granted “medical parole” after serving two months in a correctional centre in Durban.

Billions of rand have been lost to what South Africans term “state-capture” and the people charged with running the country’s key heritage sites are struggling to cope.

Jane Mufamadi is the head of Freedom Park, a heritage facility occupying 52 glorious hectares overlooking the capital Pretoria.

It was built on Nelson Mandela’s request in 2003 and honours thousands of freedom fighters who helped to challenge and dismantle the white-supremacist governments of the apartheid-era.

Yet government grants have been cut and monies from ticket sales and events have virtually disappeared.

Ms Mufamadi said: “People are no longer coming as they used to do. In terms of the numbers we are just under 10% of normal visitations.”

“Even though people can come (after the lifting of COVID restrictions)?” I asked.

“Even though people can come – so we have to go back to the drawing board,” she replied.

Ms Mufamadi does not shy away from the fact the party of South Africa’s liberation struggle, the ANC, is also the party of Jacob Zuma and host of other discredited figures. Few would choose to honour them now.

“You can see why young people are cynical,” I said.

“Yes definitely, definitely, there is no denying the fact we have challenges but we are a hopeful nation and if we could overcome apartheid we believe we can win against this.”

Source: Read Full Article