Kalloongoo’s story lays bare the horrors of slavery and subjugation

By Tony Wright

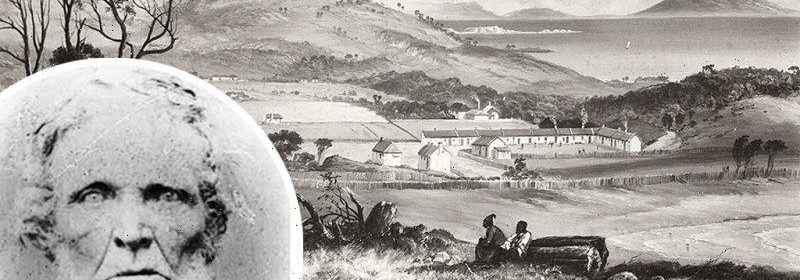

Kalloongoo finished up at the Aboriginal Station on Flinders Island in 1837 after years as a slave of William Dutton (inset).Credit:State Library of Victoria

William Dutton, a sealer and a whaler from Van Diemen’s Land, laid claim to becoming the first white resident of Victoria’s first permanent European settlement. He built a house and dug a garden in 1830 at what would become the town of Portland.

Less known is that he took as his “wife” an Aboriginal child named Kalloongoo, kidnapped from her country and sold to him as a slave.

It is no accident her story is little known.

Dutton, who is still hailed around the old town of Portland as a respected sea captain and whaler, did not broadcast that he had “bought” Kalloongoo as a young girl from a Kangaroo Island sealer.

William Dutton.

Nor did he record that he thrashed her, or that when he finally abandoned her, he took away their daughter and had her baptised, aged about six, as Sophia.

Here then is the story, long buried, of Victoria’s first colonial mixed-race “family”.

It is a story that underlines a broader verity: the new search for the truth of colonisation, the basis for Victoria’s historic Yoo-rrook Justice Commission, will be neither easy nor pleasant.

The day-to-day misery of Aboriginal women pressed or traded into the sexual and labouring servitude of sealers who operated along the Victorian coast and on the Bass Strait islands from the early 1800s, well before Europeans took to living permanently in Victoria, is not widely known.

But a record exists of Kalloongoo’s story.

She was granted the opportunity to tell it herself.

One of the most consequential and divisive figures from the early period of black-white contact in south-east Australia, George Augustus Robinson, undertook an extensive interview with Kalloongoo. Deserted and stranded on a storm-racked sliver of granite in Bass Strait, she was brought to Flinders Island in early 1837.

Robinson had been responsible for rounding up Tasmania’s dwindling Aboriginal people and removing them in the early 1830s to exile on Flinders Island, the largest of the remote Furneaux group of islands in Bass Strait.

He would become the Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Port Phillip District (later Victoria) in 1839.

George Augustus Robinson.

On islands nearby were, here and there, the survivors of the period when European and American sealers used Aboriginal women to catch and butcher seals.

Most of the women abducted or otherwise taken to sea and often enslaved by European and sometimes African-American sealers were from Tasmania.

But Kalloongoo was from the Kaurna language group of mainland “New Holland” and lived as a child on country south of what is now Adelaide, as detailed in Kaurna in Tasmania: A case of mistaken identity, a scholarly paper by Associate Professor Rob Amery, head of linguistics at the University of Adelaide.

Amery’s paper showed Robinson recorded Kalloongoo’s home country as between BAT.BUN.GER (Patpangga, now Rapid Bay) and YANG.GAL.LALE.LAR [Yankalilla] on South Australia’s Fleurieu Peninsula.

She told Robinson of being kidnapped during a raid led by a sealer named James Allan.

She was, she said, tied up, taken to Kangaroo Island and later forced aboard a schooner named the Henry, where she was sold to “Bill Dutton”.

Although precise dates are unrecorded, the kidnapping probably occurred in the late 1820s and the “sale” to William Dutton probably took place about 1830, when he was aboard the Henry on sealing and whaling expeditions and regularly occupying a house he had built in Portland.

Kalloongoo was not Dutton’s first Aboriginal female companion. During the 1820s he travelled with a woman named Renaninghe Kotaternner Puerre, who is believed to have been taken from the North George River area of north-east Tasmania.

It is not known what became of Renaninghe, although some sources suggest Dutton left her at Kangaroo Island before he settled on his new “acquisition”, Kalloongoo.

Life for Aboriginal captives on Kangaroo Island was brutal.

“She [Kalloongoo] said there were several New Holland [mainlander] black men on Kangaroo Island,” Robinson wrote in his journal.

“Said two of them died from eating seal; her brother died also from eating seal. Said the sealers beat the black women plenty; they cut a piece of flesh off a woman’s buttock; cut off a boy’s ear, Emue’s boy. [Emue was Kalloongoo’s sister-in-law.]

“This woman [Emue] is now on Woody Island [now known as Anderson Island in Bass Strait] with Abyssinia Jack [a notorious sealer, whose surname was Anderson].

“The boy died in consequence of his wounds. They cut them with broad sealer’s knives.

“Said they tied them up and beat them and beat them with ropes.”

Beatings were not restricted to Kalloongoo’s time on Kangaroo Island, either.

“Bill Dutton beat her plenty,” Robinson recorded her telling him.

During this whole period, the British Parliament was nearing the end of a long campaign to abolish slavery across the British Empire. On August 1, 1834, the Slavery Abolition Act came into force.

But distant legislation was never going to help Kalloongoo and women like her.

Kangaroo Island may as well have been a pirate kingdom in an unknown sea. The authorities of NSW, charged with administering a colony that was largely a mystery to those in Sydney, would not learn of a European settlement at Portland until late in 1836, and even then they had no way of enforcing the law at such a remote outpost.

Although details of Kalloongoo’s life with Dutton are vague, what is known is that when the Henty family arrived in Portland in 1834 – gaining a reputation for being Victoria’s first permanent residents because they brought farming implements and animals – Dutton was already there with a black “wife”.

Two weeks after Edward Henty arrived, he set off with Dutton to explore the country nearby, and wrote about it in his journal.

“… started three days’ walk in the bush accompanied by H. Camfield, Wm Dutton, five men, one black woman and 14 dogs…” Coming across an Aboriginal man, Henty recorded they “set the dogs on him”.

The woman, Kalloongoo, was called “Sarah” by Dutton. Together, they had a daughter, born about 1831.

But according to the late Portland historian Joe Wiltshire, who mistakenly identified the woman with Dutton on the 1834 trek as Renaninghe, the relatively upper-class Henty was appalled that a white man like Dutton would cohabit with a black woman, and conspired to get rid of her.

On January 5, 1835, it appears Henty got his way while Dutton was away on one of his whaling expeditions, or perhaps with Dutton’s agreement.

Henty recorded in his journal on that day that one of his ships, the Thistle, sailed for Launceston. On board was “one black woman belonging Wm Dutton to be landed at King Island … ”

Assuming Kalloongoo was cast off at King Island in Bass Strait, it remains unknown how she later found her way to Abyssinian Jack’s camp on the Furneaux Islands, further east, where she eventually ended up, in 1837, at Robinson’s settlement on Flinders Island.

Wybalenna Aboriginal Station on Flinders Island in 1893.

But she left no doubt in Robinson’s mind that Dutton – who sometimes camped with Abyssinian Jack – had dumped her.

He stated in his journal that Kalloongoo “had been abandoned by a sealer [Dutton] who had gone to Launceston and married a white woman”.

“She had a child by Dutton – a girl which he took away with him,” Robinson wrote.

And so he had.

The baptismal record No. 1005 of St John’s Church of England in Launceston reveals that on December 28, 1836, a child named Sophia, born about 1830, was baptised. Her parents were listed as William Dutton, mariner, and Sarah “an aboriginal”.

What became of Sophia remains a mystery.

Dutton married a white woman from Tasmania, Mary Saggers, in 1841. They had no children of their own, but were said to have adopted at least two.

They lived at Narrawong, near Portland, until Dutton – once a leading whaler, with 100 lucrative kills to his name – died in 1878, leaving his wife so impoverished the town’s newspaper, The Portland Guardian, publicly called for charity.

The paper recorded: “She receives orders at the Benevolent Asylum once a week for 2s. 6d. worth of bread, groceries, and other necessaries so far as the money will go, but then she sits under a rent of 2s. a week, which she is of course unable to pay, and which a kindly landlady permits to run into arrear or ‘forgives’ right out.

“Only for the kindness of a few old friends and neighbours who would not see her want for a pinch of tea or a bit of meat at times, she would ere now have perished of sheer starvation.”

Kalloongoo, however, short of friends or charity, had more journeys before her.

She was still young: Robinson estimated she was about 20 in 1837, which means she must have been 13 when she gave birth to her daughter, and could have been no more than a child when she was abducted and sold.

On Flinders Island, she kept with her a son aged about five named Johnny Franklin, whose absent father, according to Robinson’s journal, was a black sealer, possibly African American.

The boy had been born at “the Julians” – probably Lady Julia Percy Island off Portland, where Dutton had a sealing camp, or the nearby Lawrence Rocks. What Dutton had made of this we will never know.

The woman born Kalloongoo and renamed Sarah by sealers was about to be given a new name. Robinson called her Charlotte, introduced her to the Bible and made her his housemaid.

In 1839, Robinson had had enough of running the settlement for Aboriginal Tasmanians he had taken into exile with the sly promise that they would return some day to their own country.

Truganini.

Having saved about 200 Aboriginal Tasmanians from final destruction in what was called the Black War – Van Diemen’s Land’s fierce frontier conflict from 1824 to 1831 – on Flinders Island he had tried to convert these people into a European peasant culture and had failed.

With many of the exiles dying of illness and homesickness, he abandoned the settlement and moved to the Port Phillip District -– which would become Victoria – as the inaugural Chief Protector of Aborigines.

He took with him 15 Aboriginal people, including Kalloongoo/Sarah/Charlotte, and the legendary Truganini, born about 1810 on Bruny Island, who had survived terror almost impossible to imagine.

Truganini’s mother was killed by whalers, her sisters, Lowhenunhue and Maggerleede, were abducted into sexual slavery and taken to South Australia, and her uncle was shot by soldiers. A young man named Paraweena, who was to have been Truganini’s husband, had his hands chopped off and was thrown into the sea to drown as he tried unsuccessfully to prevent timber-getters from pack-raping her.

Nevertheless, Truganini joined up with Robinson in 1830 to help him try to negotiate an end to the Black War violence. She was instrumental in persuading many of the surviving Aboriginal people to move to Robinson’s settlement on Flinders Island.

Robinson intended that as he took up his new position on the mainland, his little band of Tasmanians, including Kalloongoo/Charlotte and Truganini, would help him establish friendly relations with Aboriginal people of the Port Phillip District.

It didn’t work out that way.

The Port Phillip Protectorate was established at the instigation of Lord Glenelg, British secretary of state for war and the colonies, to protect the Aboriginal people from white violence and to “civilise” them.

The idea was embraced at a time when British decision-makers were in the thrall of evangelical views about humanitarian colonisation.

But the high-minded intention of the British Parliament and the London-based Aboriginal Protection Society and the reality on the ground in south-east Australia were a world apart.

By the time Robinson arrived as Chief Protector, and four assistant protectors were appointed to help him, conflict between land-grabbing squatters and the First Peoples whose land had been stolen was well on the way to what we might call frontier warfare, complete with massacres.

Robinson, whose protectorate would last a decade before folding, soon parted ways with his small contingent of Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

Truganini set off to Westernport with a group of four others – two men, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, and two women, Planobeena and Pyterruner – possibly bent on getting square with white men, representing those who had mistreated them. Planobeena and Pyterruner had earlier been freed from the camps of sealers who had abducted them, and Planobeena had been heard to say she would teach her friends how to kill many white men.

Truganini, left, with Bessy Clark and William Lanney.

The little party raided huts, assembled a small armoury of weapons and eventually, in 1841, killed two whalers.

Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner were hanged before about 5000 people in Melbourne for the killings – the first people to be hanged in the town. Judge Willis said the executions were designed to “inspire terror [and] to deter similar transgressions”. It was a botched job, but certainly terrifying. The men did not fall the length of their ropes, and the crowd abused the executioner as Tunnerminnerwait was slowly strangled to death.

Truganini, Planobeena and Pyterruner were acquitted – thanks to an unlikely claim by Robinson that they were under the total control of the men – and returned to Tasmania.

But Kalloongoo, who had been friendly with Truganini, and once was found with her at Point Nepean living with shepherds, appears to have stayed out of serious peril, possibly because she was devoted to looking after her son, Johnny Franklin.

By 1842, Kalloongoo, kidnapped as a child from her tribal home and sold to Victoria’s first permanent resident, thus straddling the period of pre- and post-colonisation, faded from the record of the increasing violence and dispossession afflicting her people.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article