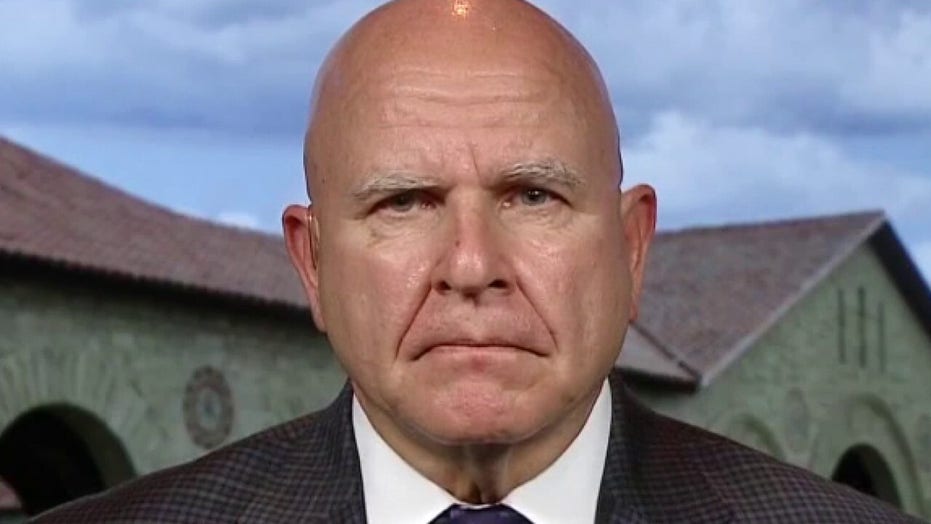

H.R. McMaster: Stop pretending Afghanistan catastrophe is anything but utter failure

H.R. McMaster: Afghanistan withdrawal a ‘humanitarian crisis of colossal scale’

Former national security adviser reacts to the chaos unfolding in Kabul on ‘The Story’

Editor’s note: This essay is adapted from the author’s congressional testimony on October 5.

The catastrophe that is only beginning in Afghanistan, is the result of incompetence based in strategic narcissism, or the tendency for American leaders to define the world only in relation to the United States, and to assume that what they decide to do is decisive in securing a positive outcome.

But others, including adversaries and enemies, also enjoy authorship over the future. In Afghanistan, policies and strategies across two decades were based on what U.S. leaders preferred rather than what the situation demanded. Strategic narcissism led to self-delusion, and self-delusion provided a rationale for self-defeat.

A fundamental lesson of Afghanistan is that wars are interactive and that progress in war and diplomacy is never linear. That is why the war in Afghanistan and the broader war against jihadist terrorist organizations is not over; it is entering a new, more dangerous era. Containing the catastrophe in Afghanistan and learning from it will require U.S. leaders to confront the truth of our experience in Afghanistan and stop pretending.

Stop pretending that our surrender to the Taliban in February 2020 and subsequent concessions to that terrorist organization—which strengthened our enemies and weakened our Afghan allies—were not the principal reasons for a lost war and its consequences.

The psychological blows we delivered to our Afghan allies included negotiating with the Taliban without the Afghan government, not insisting on a cease fire, forcing the Afghan government to release 5,000 terrorists, curtailing intelligence support, ending active pursuit of the Taliban, withdrawing all aircraft from the country, and terminating contractor support for Afghan forces.

Stop pretending that we can end so-called endless wars by withdrawal. Wars do not end when one party disengages and our enemies are waging an endless jihad. We failed to learn from our complete withdrawal from Iraq in December 2011 and the subsequent reemergence of al Qaeda in Iraq which morphed into ISIS. By the summer of 2014, ISIS gained control of territory the size of Britain and became the most destructive terrorist organization in history. As the English philosopher and theologian G.K. Chesterton observed, war may not be the best way of settling differences, but it may be the only way to ensure that they are not settled for you.

Stop pretending that all our efforts in Afghanistan were wasted. Progress is impossible to disavow as we watch the Taliban reverse gains and reinstate the horrors endured during the organization’s rule from 1996 to 2001. Afghanistan was not transformed into Denmark. But Afghanistan only needed to be Afghanistan with a government hostile to jihadist terrorists and security forces strong enough to withstand the regenerative capacity of the Taliban.

Stop pretending that the outcome would have been better if we had simply left Afghanistan after the successful military campaign in 2001. The consolidation of gains has never been an optional phase in war. The notion that the Taliban would have accepted a negotiated agreement consistent with our objectives in Afghanistan earlier in the war is just another element of our self-delusion.

Stop pretending that America cannot generate the will for sustained military efforts abroad. Sustained efforts in Korea, the Sinai, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Colombia are just a few examples of successful and sustained long term efforts. Those who cite public opinion polls that favor withdrawal should attribute lack of support to leaders’ failure to explain what was at stake in the war and the strategy for achieving an outcome worthy of the costs, risks, and sacrifices. By 2018 low levels of multi-national military and financial support were enabling Afghans to bear the brunt of the fight.

The catastrophe that is only beginning in Afghanistan is the result of incompetence

Stop pretending that there are short term solutions to long term problems. Afghanistan was not a twenty-year war; it was a one-year war fought twenty times over. Our short-term approach increased the cost and duration of the war. Declarations of withdrawal across three administrations emboldened our enemies, sowed doubts among our allies, encouraged hedging behavior, perpetuated corruption, and weakened state institutions.

Stop pretending that adversaries will conform to our preferences or that we can fight enemies we wish we had rather than our actual enemies. Until the base motivation of its Army changes, Pakistan will not be a partner against terrorist organizations. The Taliban has not changed, is intertwined with other jihadist terrorists, and is determined to reinstate brutal Sharia.

The reestablishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is as much a victory for al Qaeda and other jihadists as it is for the Taliban. The notion of partnering with the Taliban to fight terrorism is like partnering with Whitey Bulger or Tony Soprano to fight organized crime.

Stop pretending that vilification from the ‘international community’ will influence the Taliban. The notion that enemies of humanity who are determined to force Afghanistan back into the 7th century or an organization led by Hibatullah Akhundzada, who encouraged his seventeen-year-old son to commit murder as a suicide bomber at age 17, are concerned about chiding tweets or disapproving speeches is ludicrous.

Stop pretending that the military instrument can be separated from diplomacy. As Secretary George Shultz observed, “negotiation is a euphemism for capitulation unless the shadow of power is cast across the bargaining table.” Civilian and military leaders said that there was no military solution to the war in Afghanistan. But the Taliban, their Pakistani sponsors, and their al Qaeda allies clearly came up with one. More diplomacy with the Taliban without the prospect of force will achieve nothing but further embarrassment.

Finally, we must stop pretending that it is acceptable to fight wars without a commitment to win. Winning in Afghanistan meant achieving the just intention of ensuring that Afghanistan never again became a haven for jihadist terrorists. Because in war each side tries to outdo the other, lack of commitment to win is counterproductive. According to Thomas Aquinas’ jus ad bellum theory, it is also unethical to fight without determination to succeed. Our leaders invented new terms like ‘responsible end’ as cover for their ambivalence as they sent soldiers into battle.

Unless we stop pretending and demand better from our leaders, the prospect of learning from our searing experience in South Asia, rebuilding our strategic competence, and effacing the stain of 2021 will remain dim.

This essay is adapted from October 5, 2021 Congressional testimony.

Source: Read Full Article