Biden's first year: Tracking the US economy's recovery from the pandemic

Moody’s Analytics chief economist on when inflation should moderate

Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi explains what he believes is contributing to rising inflation and what could tame it.

President Biden began his campaign in 2019 with a simple, if vague, promise to voters: He would return the country to the status quo if elected.

Then came the coronavirus pandemic, which thrust the U.S – and the world – into unprecedented times, triggering the deepest, but shortest, recession in nearly a century as millions of Americans lost their jobs or were furloughed. Biden pivoted: if elected, he pledged to pass a sweeping, multitrillion-dollar agenda that would reshape the economy and shore up the middle class.

But it has been slow progress in the one year since Biden was officially inaugurated: While the U.S. economy is growing at a solid pace, it faces challenges in the year ahead from repeated COVID-19 outbreaks, the hottest inflation in nearly four decades, a labor shortage and supply-chain bottlenecks.

Here's a closer look at where the economy stands, one year into Biden's presidency:

Employment

Over the course of the past year, the economy has recovered about 6.4 million jobs, or an average of 537,000 per month – more than in any year on record. But the nation remains 3.6 million jobs short of pre-pandemic levels in February 2020.

"It's a historic day for our economic recovery," Biden said in brief remarks from the White House following the December jobs report. "Today's national unemployment rate fell below 4% to 3.9%, the sharpest one-year drop in unemployment in United States history … Years faster than experts said we'd be able to do it, and we have added 6.4 million new jobs since January of last year."

WHERE ARE SURGING CONSUMER PRICES HITTING AMERICANS THE HARDEST?

Wages are up 4.7% over the year and there are roughly 2 million Americans collecting unemployment benefits, compared to the 20 million who were receiving aid last year, before the vaccines were widely available.

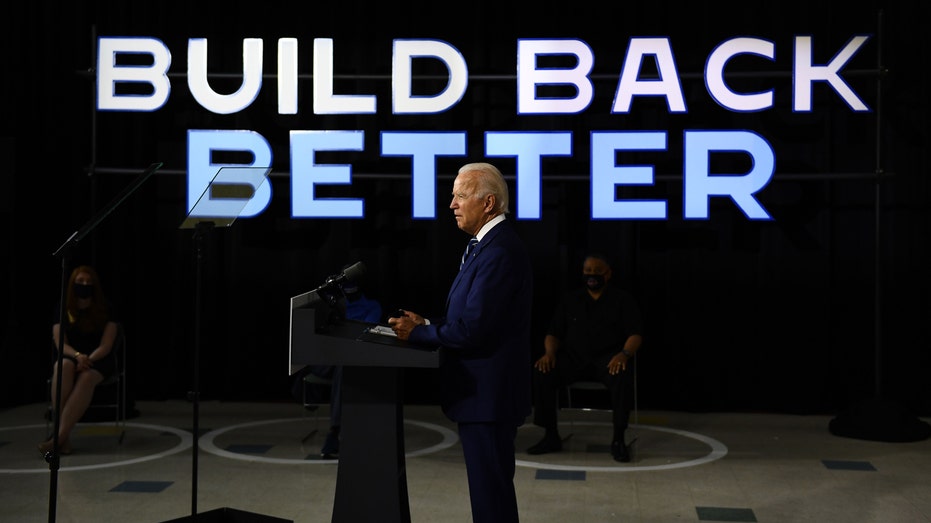

A man wearing a mask walks past a “now hiring” sign on Melrose Avenue amid the coronavirus pandemic on April 22, 2021, in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images / Getty Images) Still, hiring has often been slower than experts anticipated – and many have chalked it up to a dearth of workers, rather than languishing demand. A record number of Americans have been quitting their jobs as they seek out higher wages, better working conditions or more ideal hours. At the end of November, there were 10.6 million open jobs, far more than the 6.9 million unemployed workers. The number of available jobs has topped 10 million for six consecutive months; before the pandemic began in February 2020, the highest on record was 7.7 million. "I think a lot of people are looking to better themselves," Biden's labor secretary, Marty Walsh, said recently. "They're quitting the job that they're in, and they're going to be looking for better-paying jobs and more opportunities." American consumers are contending with the hottest inflation in close to four decades, with the cost of everyday necessities like food, rent and heating oil surging in recent months. And there's no evidence the inflation spike is subsiding: Earlier this month, the government reported that prices for U.S. consumers surged 7% in December compared with a year earlier, the fastest increase since June 1982. Rising inflation is eating away at strong gains and wages and salaries that American workers have seen in recent months: Real average hourly earnings rose just 0.1% in December, as the 0.5% inflation increase eroded the 0.6% total wage gain, according to the Labor Department. On an annual basis, real earnings actually declined 2.4%. President Joe Biden delivers an opening statement during a news conference in the East Room of the White House on Jan. 19, 2022, in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images / Getty Images) The price squeeze has been bad news for Biden, who has seen his approval rating sink to a historic low as prices rise. Although both the White House and the Federal Reserve insisted that soaring inflation was merely a weird side effect of the rapid economic reopening and would likely fade as shipping delays and temporary supply shortages abated, they have since acknowledged it is a real problem that needs to be addressed. FED DOUBLES TAPER RATE, EYES THREE INTEREST RATE HIKES IN 2022 The question now is whether the president can tame the root causes of inflation – supply-chain disruptions and labor shortages – ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. "We have faced some of the biggest challenges that we've ever faced in this country these past few years, challenges to our public health, challenges to our economy. But we're getting through it," Biden said Wednesday during his second White House press conference. "And not only are we getting through it — we're laying the foundation for a future where America wins the 21st century by creating jobs at a record pace, and we need to get inflation under control." The Fed has also radically changed course over the past month and pledged to normalize policy in order to quell the inflation spike. "If we have to raise interest rates more over time," Powell told the Senate Banking Committee during his confirmation hearing earlier this month, "we will." U.S. economic growth started off strong in 2021, expanding at an annual revised rate of 6.4% in the first quarter and 6.7% in the second quarter. But a wave of COVID-19 infections in the summer driven by the highly contagious delta variant forced consumers to pull back on spending, weighing on growth. Pre-owned automobiles are shown for sale at a car lot in Oceanside, California, Oct. 3, 2016. (Reuters/Mike Blake / Reuters Photos) In the third quarter, the economy grew by just 2.3% on an annualized basis. It marked the slowest pace since the second quarter of 2020, when the economy was still in the throes of the shortest, but steepest, recession in nearly a century. The third-quarter slowdown also reflected pandemic-induced disruptions in the supply chain that limited the availability of goods such as motor vehicles, as well as the evaporation of federal stimulus money provided to businesses, households and state and local governments. GDP Now, an up-to-date tracker monitored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, is currently estimating fourth-quarter growth of 5.1%. Wall Street forecasters are dialing back their growth projections for 2022 as hopes fade for Biden's sweeping economic agenda and concerns grow about the new COVID-19 variant. Biden began his presidency with grand ambitions of approving nearly $4 trillion in federal spending that would be used to dramatically expand the government-funded social safety net and combat climate change. Then-presidential candidate Joe Biden speaks about on the third plank of his Build Back Better economic recovery plan for working families, on July 21, 2020, in New Castle, Delaware. (Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images / Getty Images) The president secured early victories with a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package that Democrats passed in March and a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill that includes $550 billion in new funding for traditional projects like roads, bridges, public transportation and broadband. CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS But the parts of Biden's economic agenda that were intended to cement his legacy as a modern-day Franklin D. Roosevelt have languished in the Senate. The initial proposal from Biden imagined funneling more than $2 trillion to progressive priorities like free community college, expanding Medicaid, establishing universal kindergarten and paid family leave, all while being funded by a slew of high taxes on rich Americans and well-off corporations. Biden spent months in torturous back-and-forth negotiations with the moderate members of his caucus, and though it seemed like there could be a deal for a scaled-back bill at the end of the year, Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia abruptly withdrew his support, citing hot inflation and geopolitical uncertainty. The plan's chances have plummeted since then, although Democrats are hopeful they can pass a much narrower bill this year. Source: Read Full ArticleInflation

GDP

Government spending