US economy added 916,000 jobs in March

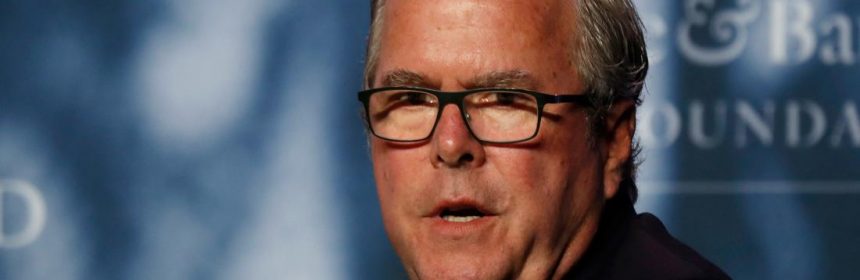

Jeb Bush is the 43rd governor of Florida and founder and chairman of ExcelinEd. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own.

America doesn’t have a jobs problem. It has a pathways-to-jobs problem problem. Our economy is producing jobs — there were 7.4 million open jobs as of February in the midst of a pandemic — but our education system isn’t preparing people to fill those jobs.

What’s worse, our workforce policies do a poor job of retraining people for the workforce of tomorrow. According to a study by PwC, roughly three out of four working Americans are ready to learn new skills to stay employable, but government-sponsored job training programs have a mixed-to-poor track record.

Most Americans get the best education they can afford when they’re young and then start working. But they don’t stop there. They might take on a part-time gig, go back to school, take a few stretch assignments or follow the advice of a mentor.

But is that DIY model going to work as a growing number of Americans face the risk that their job path might be closed off by automation, artificial intelligence and other technologies?

I don’t think so.

The problem is that our workforce and career preparation programs, in our school systems, colleges and various technical training centers, fail most Americans who want to better themselves.

Americans want more options. They want education when they can squeeze it in, not just during the hours when schools are open. They want online training focused on skills they can use right away. In short, people want to actively manage their careers by gaining degrees and building credentials as necessary and as they go.

A new model for college and career preparation would have more measurement, more accountability, more relevancy and more flexibility.

Where the Covid stimulus package went wrong

A tax on financial transactions could rein in Wall Street’s greed

The pandemic won’t be the end of movie theaters, but it will forever change them

It would continue to treat the four-year degree as a primary goal for all, but not to the exclusion of other high-quality and respected pathways. After all, college isn’t always the right place to learn for 18-year-olds; some students might benefit from earning a valued credential and some work experience first.

We need to link learning and work-preparation programs from K-12 through college and early career stages. ExcelinEd, an organization that supports state leaders in transforming education, has launched Pathways Matter, the first and only comprehensive suite of policy solutions for all 50 states with research and case studies created for this level of change in education. This new tool can help state leaders design and implement student-centered, state-based policies to build a skilled and educated workforce, with the following key strategies:

First, we need to build more ways for students to accelerate their postsecondary education without the need to be on a campus. Students can start earning college credits through Advanced Placement, dual enrollment and International Baccalaureate programs while still in high school. Distance and virtual learning can deliver to students the fruits of learning without the expensive, in-person campus experience.

Second, we need to involve industry more strategically. For example, a relevant program in systems engineering, co-designed by companies in need of IT engineers, would prepare hundreds of students each year for a high-growth career. It would also lead to other mini-degrees that would stack one on top of the other or to a registered and paid apprenticeship program. Either way, we have to do far more to train people for the millions of “middle-skill” job openings — think sales, construction, repair, transportation — that either exist now or will exist soon and that require some kind of post-high school education but not college.

Third, we must do a better job of creating real options for people whose careers are threatened by automation. According to the World Economic Forum, automation could replace 85 million jobs in five years. Most minimum wage jobs are going to be automated, so we should be focusing on educating workers to enter the workforce at well-above the minimum wage. Employers are looking for those types of workers anyway.

If someone demonstrates the potential for a high-growth, high-paying career, they should be able to count on “last dollar” tuition assistance for the specific training they need. Nearly 36 million Americans are part of the “Some College, No Degree” population — meaning they have some postsecondary education and training but did not finish and are no longer enrolled. A state can enact a policy to provide that “last dollar” to cover tuition to complete a degree.

Some examples of these types of pathways already exist. In Tennessee, high schools, technical colleges and employers are encouraged to coordinate how they value course credits so that students can expect good-paying work in growing industries, even without a bachelor’s degree, and a potentially higher salary if they gain additional certifications and college coursework.

The Texas State Technical College, with its 10 campuses, is a top producer of engineering-related associate degree earners. The program is funded based on whether graduates are placed in jobs and how much they earn in wages above minimum wage, rewarding the school for helping students earn more.

What would this look like in states across the nation? Learning would be available through private industry-sponsored academies and community colleges alongside union-sponsored apprenticeships.

With better education-to-workforce pathways, military veterans and others would be able to get course credits for demonstrated skills and prior work experience. It would be easy to enroll in apprenticeships and work-study programs. When people need a few more college credits to graduate or get a certification, they could get it affordably.

At the heart of all these efforts would be a simple recognition of reality: There are very few workers in America today who can afford to do the same task and expect the same pay, year after year. It’s a dynamic world, and America remains a dynamic place.

It’s time our workforce programs respond as well. For too long we have allowed workforce preparation programs — starting in our public schools and extending into community colleges and elsewhere — to stay on auto-pilot, largely unchanged and unresponsive to the changes happening all around them.

We could be doing a lot more to help Americans learn the skills to earn a living and make their way in the world, independently and free from debt.

Source: Read Full Article