The Other ‘Satan Shoe’ Drops: Lawyers Size Up Nike’s Settlement With MSCHF

Nike may have settled its lawsuit with MSCHF over the collective’s Lil Nas X “Satan Shoes,” but the controversy leaves lots of questions for both brands looking to be more litigious and for resellers.

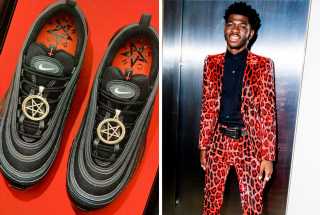

After being granted a temporary restraining order on April 2 to halt the sale of 666 pairs of the $1,080 “Satan Shoes,” Nike’s settlement calls for MSCHF to initiate a voluntary buyback of the shoes, which were reimagined Nike Air Max 97s that featured an engraved bronze pentagram; the Bible passage Luke 10:18, which details Satan falling from Heaven, and one drop of blood in the sneaker’s air bubble sole that was provided by MSCHF staffers. The settlement also calls for a voluntary buyback of MSCHF’s “Jesus Shoes,” which were also made from Nikes and were sold in 2019.

A day after the launch, Nike filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court in New York against MSCHF, a Brooklyn-based art collective, on March 29 for trademark infringement, false designation of origin, trademark dilution, common law trademark infringement and unfair competition over the sneaker. Although Nike was not involved with the Lil Nas X collaborative sneaker, the sneaker giant faced social media backlash.

In a statement at that time, Nike noted that MSCHF altered the shoes without the company’s authorization. Such creative license is rampant in the resale market, especially among sneaker heads. Nike noted that “if any purchasers were confused, or if they otherwise wanted to return the shoes, they could do so for a full refund.” Consumers also have the option of keeping them.

Related Gallery

Photos of Vivienne Westwood’s Career From the Fairchild Fashion Archives

Asked about the potential for the Nike settlement to encourage other brands to take legal action regarding trademark tarnishment, Rebecca Tushnet, professor of First Amendment law at Harvard Law School, said, “Tarnishment as a doctrine is deeply constitutionally suspect, and the settlement merely extended the arrival of the day of reckoning.”

She noted that “Nike asserted — and the court apparently saw — both confusion and dilution, rather than dilution alone. It is rare that a dilution claim on its own succeeds.”

David Bernstein, a Debevoise & Plimpton attorney representing MSCHF, reportedly said the shoes “were never about making money” and were made “to make a point about how crazy collaboration culture has become.”

Speaking by phone Friday, Bernstein said he was not surprised by the outcome because the request for the injunction came too late. He noted how nearly all of the 666 pairs of shoes had been sent out to “the collectors” by the time the court heard the motion for the temporary restraining order. (Plans for Lil Nas X to give away one pair of shoes was put on hold once the lawsuit was filed, Bernstein said.) He said, “It’s unfortunate that the first my client learned about this was a lawsuit. They never received any objections back in October 2019, when they released the Jesus shoe. They never heard from Nike prior to being served with a lawsuit. Had Nike reached out, I don’t know what the result would have been.”

MSCHF “had made clear all along” that the limited edition would only be 666 pairs of shoes. “From their perspective, it was already over,” he said, adding that Nike’s request for a recall at the temporary restraining order hearing was denied by the court at that time.

The lawsuit has “brought extraordinary attention to MSCHF and what it was trying to achieve with these artistic shoes,” Bernstein said. “I expect the value of these shoes will have grown exponentially thanks to all the controversy as a result of the lawsuit.”

MSCHF has another drop coming up in the next few days. As for whether the lawsuit will make MSCHF more cautious in the future, Bernstein said, “I don’t think that there is any reason that they need to be more cautious. MSCHF was entirely within its rights under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution to express themselves through these artistic works. There’s no basis for them to think that they need to be more cautious. They have every right to exercise their First Amendment rights just as we all do.”

Media requests sent to MSCHF’s founder Gabriel Whaley were not acknowledged. Officially known as MSCHF Product Studio Inc., the company specializes in viral projects and was started in 2016. MSCHF has received a slew of free worldwide publicity in the past two weeks due to the controversy. And Lil Nas X has topped the Billboard Hot 100 with his latest song, “Montero (Call Me By Your Name).”

After the late March launch, the “Satan Shoes” reportedly sold out within minutes. How many, if any, consumers agree to return their footwear for the MSCHF-led voluntary buyback remains to be seen. The round-the-world publicity has only increased the value of the footwear.

Artists, start-ups and designers appropriate, interpret and reimagine logos and brands without consent on a regular basis. And consumer demand for such individualistic pieces is only increasing. Auction houses have gotten in on the collectable sneakers trend, including Sotheby’s and Christie’s, which sold a pair of Michael Jordan’s game-worn Nike Air Jordans for $615,000 last summer.

Addressing Nike’s settlement, Stanford University Law School director Mark Lemley said, “I think Nike would have had a hard time making the case that people thought they were selling or authorizing the sneakers. This doesn’t seem like a big win for Nike unless there are other terms I don’t know about. This may be a way for them to save face, since a voluntary buyback of sneakers that are already sold doesn’t change much, and may actually raise the profile of the shoes on the secondary market.”

Notre Dame University Law School professor Mark McKenna described the case “as more of a p.r. issue for Nike more than a real trademark issue. One piece of evidence is the previous iteration of ‘Jesus Shoes,’ and they didn’t object to those.”

From his perspective, Nike recognized that the “Satan Shoes” were more of an art project than a matter of selling shoes. Noting how trademark law allows for the buying of authentic shoes and modifying them for resale, the constraint is that material changes are normally not allowed on the goods, McKenna said. However, most of the changes were not modifications to the structure of the shoes, “they were doing this avant-garde speech thing,” McKenna said.

After getting a lot of blowback from some customers, Nike wanted to be seen by its customers as doing something about the situation, he said. After getting a temporary restraining order, they settled the case within days. A company that was really aggressively trying to enforce its trademark probably would not have settled that kind of case immediately unless they get a full capitulation from the defendant, McKenna said. “I doubt they got that.”

Whether consumers will agree to return any of the purchased “Satan Shoes” to MSCHF remains uncertain. (As of Sunday afternoon, multiple pairs were available online for as much as $15,000.) They are not obligated to do so, because they didn’t do anything illegal and are not a party to any action, McKenna said. “Somebody who bought these and has them in their apartment can’t really be forced to turn them back over. I think they mean more that if they are sitting in stores on shelves and haven’t been purchased by someone, you can go reclaim them and destroy them.”

The Nike-MSCHF controversy presented “a plausible art/free speech argument to be made here,” McKenna said. “Trademark doctrine has some tools here to recognize that. But it’s sometimes harder for courts to see the artistic component when it’s selling what looks to them like an ordinary commercial product. There were plausible claims there, but it was precisely the message of the shoes that Nike didn’t like.”

McKenna, who is also director of the Notre Dame Technology Center, found that “telling, because the ordinary kinds of harms that trademark laws are concerned with are not harms that have to do with the speech message of the product. Although there are definitely circumstances where that’s the clear motivation of the trademark owner,” he said.

While many people can see from Nike’s perspective what they were bothered by, McKenna questioned “the idea that [trade]mark owners get to police the viewpoints and expression that people are using their brands to make. They didn’t object to the ‘Jesus Shoes,’ but they do object to these. That should be worrying because it signals the willingness to say, ‘Only we get to speak about what our brand means and no other persons do.’ That can certainly be problematic. If people are trying to make comments about the company and their labor practices, we would have normally had thought of that as an ordinary speech right. In this case, it gets bound up by the fact that they’re doing it by reselling Nike shoes. We live in a world of Instagram and lots of collaborations with artists. Nike’s viewpoint is we constantly work with artists, no one will know if this is one as well.”

As reported earlier, Nike faced criticism from the U.S. Postal Service for the upcoming USPS Experimental Shoe, which carries a stamp inspired by the Priority Mail shipping label. The footwear was neither licensed nor otherwise authorized by the USPS, which struck back publicly against Nike. The Postal Service issued a statement that noted the USPS receives no tax dollars for operating expenses and relies on the sale of postage, products and services to fund its operations and protect its intellectual property.” Asked Friday if anything has been decided about taking legal action, a USPS spokeswoman declined to comment.

McKenna described the USPS shoes as “a little revealing,” noting how it made the prospect of mistaken collaborations argument “bogus.” He said, “Obviously, there’s some irony in the fact that nobody gets to use their trademark to make some kind of collaborative point, but they get to do it and they don’t have to pay anything else to do it.”

Had the Nike case been litigated all the way through, it could have cost “hundreds of thousands of dollars if not more,” McKenna said. “Sometimes it is precisely the cost of that litigation that encourages defendants to fold really quickly. Even if they are likely to be successful, they might have to spend a lot of time and money on the case to get to that result. It might not be worth it to them. They might just walk away.”

He said, “While the doctrines in trademark law do not always give a defendant a direct route to a win, even when ultimately they are likely to win, those are definitely carrots for brands to enforce when things are a little questionable.”

Last year, Rolex won a copyright infringement case against La Californienne, which had repurposed the luxury watches with colorful faces and bands. La Californienne’s cofounder Courtney Ormond declined to comment Friday.

Highlighting how cases in the U.S. have three stages — the temporary restraining order, the preliminary injunction and the final injunction after trial — Christopher Stothers, partner of intellectual property, data and commercial at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, said, “Nike made the first of those three and then the case settled. It’s not the most extensive legal record, but it’s obviously a very extensive public domain record.”

From his perspective, two movements have been underway in the U.S. recently — one toward allowing genuine goods to be resold more freely and the other (as in the case of the “Satan Shoes”) being on changed goods. While there had been less focus on the resale of changed goods previously, “there obviously is more on it now,” Stothers said.

”Obviously, this is an exceptional case in terms of the way the goods were modified. Few brands would be happy seeing their good modified in that way. Clearly, customization and particularly changing of fashion goods is happening more and more not just with individuals doing it, but individuals doing it for resale,” he said.

To what extent that will change based on this case is difficult to say, according to Stothers. Nike’s lawsuit “will give encouragement to brands that have a problem with it. But brands have to be very careful how they play this. There is a lot of policy. Put aside the legal point. That’s all interesting for the lawyers. The question for the brand is, ‘Do they want to be seen as interfering with what their customers do with their products?’”

In this “relatively easy case, they could say what was happening was bad,” said Stothers, adding there “were great examples in the complaint of customers’ responses being extremely negative.” He added, “However, that may not be in the case with someone who is customizing goods in a way that the brand does not like, but does not involve using human blood, Satan and so on…”

While the Nike case provides some encouragement to other brands looking to take action, “the challenge for brands will be ‘Do you want to do it and what cases will you take?’” Stothers said. “Just because you can do it, doesn’t mean it’s a good commercial decision to do it by bringing cases to the courts.”

Companies have a good deal consider from his standpoint.

“When you’re bringing an action as a lawyer, you’re looking for good test cases. When you’re bringing an action as a brand or a company, you’re thinking about, ‘What’s the fallout of this case going to be?’ ‘What’s the press going to say about it?’ Particularly, if you’re a big, strong brand, are you going to be seen as bullying or as properly defending your brand?” he said.

While there is a massive pool of resellers globally, taking legal action against someone reselling a pair of unchanged sneakers “is very difficult to do,” said Stothers, noting how the Nike lawsuit dealt with altered products.

As for the firestorm of publicity and media coverage that the lawsuit generated, he said he was not really surprised. “Everybody is looking for interesting news right now that is a bit different from vaccines and so on.”

As a test case for someone altering sneakers, this was an obvious one to do, Stothers said, noting how the other side seems to be satisfied. “They got a lot of publicity out of it. Whether they see it as a disaster or a success, I’m not sure. Certainly, both sides are claiming it as a success.”

Source: Read Full Article