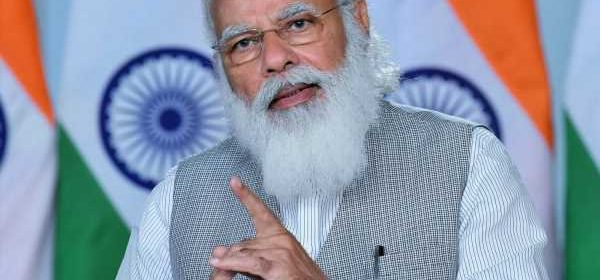

Is Modi stepping onto a minefield?

A faltering economy may have led to a re-think on economic strategy.

And Mr Modi might think he is politically strong enough to take some risks.

But there could be a minefield ahead, alerts T N Ninan.

Narendra Modi’s approach to economic issues has changed, the dividing marker being the 2019 re-election with an improved majority 21 months ago.

Having also gained control of the Rajya Sabha, he has become progressively more ambitious about pushing through long-delayed economic reforms, confident enough to change direction if needed, and willing to challenge the conventional wisdom.

His government’s bold announcement of a sweeping privatisation policy (sell or close all non-strategic government companies) follows the replacing of restrictive labour laws and the opening up of agricultural marketing.

Touchy subjects, all of them.

In the process he has trodden on what states consider their turf.

Where once he retreated in the face of Rahul Gandhi’s jibe about a ‘suit-boot ki sarkar‘, he has now embraced the role of private enterprise, launched a well-aimed attack on the permanent civil service, and limited the role of the public sector to four strategic sectors.

Amazingly, he has done so in the midst of an ongoing farmers’ agitation that is driven by the fear of corporate interests taking control of agricultural markets.

There is no mistaking Mr Modi’s new willingness to stake his position although some of what he proposes could prove as contentious as the new laws on agricultural marketing, and no easier to implement.

There is no hedging of bets here.

Mr Modi has also abandoned his fiscal conservatism and adopted a more expansive stance on both deficits and public debt.

And while the lack of faith in inherited free trade agreements was evident even in the first term, and the ratcheting up of tariffs began then, the launch last year of the atmanirbhar campaign showed a more open willingness to disregard the received wisdom in economics while re-thinking the ‘Make in India’ strategy.

The prime minister is no longer shy of showing his real hand — as evident also in the aggressive moves to change the status of Jammu and Kashmir and introduce new citizenship laws.

The change of economic stance shows in his re-focusing government expenditure on capital investment, persuaded by the logic that this delivers a bigger growth multiplier.

What has been given up, in the bargain, is any real increase in the budgets for his earlier focus area: Universalising a range of goods and services and expanding the safety net.

Just when the pandemic has rendered millions jobless, and almost certainly reversed the steady if slow decline in poverty headcount numbers, this shift in the expenditure pattern is striking.

Equally noteworthy is the blunt refusal, in the context of growing inequality, to look for redistribution through taxation policy and fiscal transfers.

With every step, Mr Modi is striding out in new directions.

One can but speculate on the reasons for the change in approach.

Perhaps it is that the ruling party has control of the Rajya Sabha — which it did not have when the Modi government sought unsuccessfully, in 2015, to change land acquisition laws.

Perhaps the faltering economic growth numbers even before the pandemic have led to a re-think on economic strategy.

This might also explain the willingness to put aside concerns about the environment, in order to press ahead with building the economy’s physical infrastructure in even ecologically fragile areas like the Himalayas.

The privatisation thrust could well be born out of frustration with the government’s banks and their endless need for fresh capital, as also by revenue considerations since both tax and non-tax revenue have fallen in relation to gross domestic product.

Finally, Mr Modi may think that he is politically strong enough to take a few risks.

And risks there are.

Despite the successes achieved and changes engineered after the 1991 reforms, much of India still draws mental comfort from a soft-State omnipresence that cossets even as it constricts and corrupts.

Most of the private sector comprises small enterprises; there are only a handful of large business entities capable of putting out the money to buy government-held corporate assets.

That makes privatisation a fraught enterprise.

The new fiscal stance risks inflation — traditionally the economic issue that turns voters against a government.

And if the bet is on growth, what if growth disappoints? Mr Modi is stepping onto a minefield.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article