How did Nirav Modi pull off PNB fraud?

Theoretically, Modi, who understood corporate finance, committed no crime by raising debt to fund a growing business.

In fact, he did a tidy job of it, but his operation started to see the ground underneath it give way in January 2018.

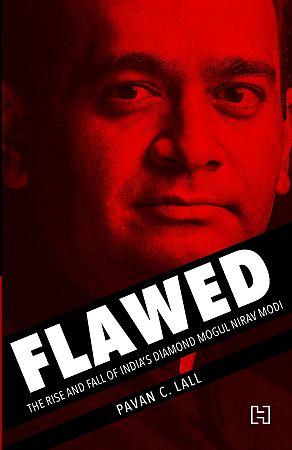

A fascinating excerpt from Pavan C Lall’s Flawed: The Rise And Fall Of India’s Diamond Mogul Nirav Modi.

Nirav Modi wanted to import jewels and make world-class jewellery, for which he needed finance.

He didn’t want to opt for a rupee loan, because it was expensive and there was a foreign currency risk.

What he wanted was a foreign currency loan which was cheaper.

Theoretically, Modi, who understood corporate finance, committed no crime by raising debt to fund a growing business.

In fact, he did a tidy job of it, but his operation started to see the ground underneath it give way in January 2018.

That’s because he did make interest payments on and off to PNB until December 2017, after which repayment of any kind stopped altogether.

The alarm bells were sounded, and deeper and more worrisome questions emerged when Modi’s loans were scrutinised.

How did he secure bank loans without having a loan account and other related sanctions such as limits, collateral and so on?

In a manner, he leapfrogged it by procuring a guarantee from Punjab National Bank in the form of LoUs for cheap, short-term foreign currency loans that were geared in the main for importers, but without putting any collateral down — and that’s where the first hint of impropriety should have sent warnings through the entire system.

Normally an LoU issuer will ask for a margin, which can be as much as 100%.

Sometimes even more. Why on earth would an importer offer such a high margin?

The short answer is that a margin or ‘collateral’ would typically be retained with the LoU-issuing lender in the form of a fixed deposit, the return of which would be higher than the cost of the forex loan.

But for reasons best known to its management, PNB never asked for margin.

When asked why, PNB’s management offered no answer.

As of June 2018, approximately 150 LoUs remained outstanding and unpaid, totalling more than a billion dollars, but that amount would also change later.

What also remains unanswered is how so many unauthorised, unaccounted and unscrutinised loans evaded enquiry for so long.

It was when one of the key accused, PNB’s Deputy Manager Gokulnath Shetty, retired that things fell apart, because he wasn’t present to sign off on forged documents.

Before he retired, Shetty signed off on loans and letters of credit in exchange for bribes that enforcement directorate officials said were not even remotely in tandem with the amount of money the LoUs raised.

The other PNB employees accused were Manoj Kharat, a single window operator who helped Modi get the LoUs by working in collusion with Shetty; Bechu Tiwari, manager of PNB’s foreign exchange department; Praful Sawant, a loan officer whose job it was to reconcile core banking solution entries and SWIFT messages but hadn’t done so; and Yashwant Joshi, a manager in the forex department.

Tiwari supervised Shetty’s and his manager’s work to ensure SWIFT entries, and was fully aware of what Shetty was up to.

Joshi was also responsible for supervising Shetty and ensuring daily reports were made of SWIFT and CBS entries.

He also knew about Shetty’s activities but took no action.

Sawant was responsible for checking the SWIFT messages daily and updating his managers.

Modi’s employees may have come to the bank for an LoU, but this time around the new official in-charge followed the rules and asked for collateral.

Accustomed to obtaining LoUs fraudulently since 2011, without observing any required banking stipulations, the sudden waving of the rulebook threw Modi’s team off balance, and all that they could manage was a feeble response, which was that they had never had to do any of that in the past.

How they managed to keep the whole scheme from being discovered for almost a decade has to do with more than just the interest payments that were made to the bank.

It speaks of a potentially deeper collusion within a banking system that involved not just one State-run bank but also foreign banks, where officials would have had to have some inkling of what was happening.

This means that Modi may have started out legitimately but at some stage went rogue and subverted the system, figuring that he would be able pay it all back once his company went public.

Either way, his team’s response caused a stir and when officials at PNB scanned their databases and found no trace of any past transactions, it led to a widening probe.

What emerged was that the bank had issued hundreds of unauthorised LoUs to Modi as well as his uncle Mehul Choksi over the past seven years.

The LoUs, once received, were cashed out abroad from branches of different Indian banks.

PNB’s announcements went on to say, ‘The companies were maintaining only current accounts with the branch and were not enjoying any fund/non-fund-based limits. None of the transactions were routed through the CBS system, thus avoiding early detection of fraudulent activity.’

Shetty said in a confession to the enforcement directorate that he first issued an LoU to Modi in 2010 and that all the LoUs after that, collectively worth around Rs 13,700 crore, were issued by him.

According to the team at BDO India, the accounting firm appointed by PNB to audit Modi’s companies and businesses, there were a total of 1,561 LoUs issued by PNB to the Nirav Modi group with the vast majority going to related companies in Hong Kong and the Middle East.

The total funds authorised through LoUs was Rs 28,000 crores of which 1,381 were fraudulent LoUs and worth around Rs 25,000 crores.

As of the FIR date, February 2018, 161 LoUs were unsettled, which in turn were worth Rs 6,247 crore.

Shetty later said that the grand design was pushed through by Rajesh Jindal, general manager of PNB’s Brady House branch between 2009 and 2011, and later general manager, credit, for PNB in New Delhi.

Shetty revealed that Jindal was the one who started the whole show with four LoUs that waived the margin, under the pretext that it (the margin) would be forthcoming, and that he had forced Shetty to issue the unsecuritised LoUs.

Shetty also said Modi and his uncle Choksi had blackmailed him during the years after Jindal left, threatening to make his actions public, which is why he continued issuing the letters until 2017.

Shetty took total responsibility for his actions and said none of his junior employees were aware of the fraud, but that remains altogether too easy to believe.

Was it truly just one man or two who subjected PNB to such massive a fraud?

How was it possible for other members of the credit team to not notice the wrongdoings and hit the panic button when they realised what was going on?

Shetty, who was with PNB for some 36 years, was promoted just once before his retirement, which is odd.

Stranger still was the fact that he was never transferred from his post in almost four decades in a profession where moving across the country is commonplace.

How did he stay in the same city, in the same branch, with the same designation, for so long?

Was it not out of the ordinary and was it designed by others in the system to keep him in a certain place?

According to data that PNB shared, before his retirement, Shetty went on a rampage to issue some 143 LoUs in just two months starting on March 1, 2017 — seven LoUs short of the total issued over seven years since 2011, when the alleged fraud began.

Experts say in most banks the SWIFT system, used for international transactions, and CBS work separately.

In PNB’s case, the outstanding LoUs were not recorded on its CBS because it was being run on Infosys’s outdated version of the Finacle software.

PNB even went on to suggest that it suspected officials at foreign branches of other Indian banks that extended credit were also in the know.

Despite earlier claiming that it was just a people issue, PNB officials finally admitted that they ‘have been working on plugging gaps and improving checks and balances. SWIFT has now been linked to CBS and the bank has upgraded to a newer version of Finacle.’

The spokesperson maintained, ‘To prevent similar frauds, the bank has segregated the front-line and back-office functions, and all foreign exchange transactions are now being processed at the back office itself so that the risk of people failure is minimised. Similarly, for credit, different verticals for processing, monitoring and recovering have been created.’

Regardless of software upgrades or the lack thereof, to swindle a bank requires more than one conspirator.

In general banking, there are three people who operate SWIFT messages: The maker, the checker, and the verifier or authoriser.

Banks worldwide use SWIFT to send data and instructions through coded messages.

The maker punches the message into the system, the checker vets the message and, in stage three, the verifier transmits it to the recipient bank after its authenticity is proven.

But the buck doesn’t stop there.

After the SWIFT message is sent to a foreign bank for a particular transaction, the bank which receives it and transfers the money (to the overseas nostro bank account of the company, where one bank’s money is held by another bank) plays back a SWIFT message to confirm the existence of the loan.

The person who receives that message is different from the maker, the checker and the verifier, and the message comes into a secured room to which not everyone has access, and it is even printed on a separate printer.

If Shetty was the only villain in the fraud, he had somehow become all four — maker, checker, verifier and the receiver of the message, confirming the creation of a loan.

That would be believable if he was indeed the senior-most employee across three or four departments related to the LoUs or the overarching authority figure in the branch — but he was neither.

Unless, of course, he had become all four by forging documents and signing in with passwords intended for other officials.

Excerpted from Flawed: The Rise And Fall Of India’s Diamond Mogul Nirav Modi by Pavan C Lall with the kind permission of the publishers, Hachette.

Source: Read Full Article